Most Californians might think that the nut is the most useful thing to come from an almond tree, but the Almond Board of California is funding research that sheds new light on co-products of the crop.

California almond orchards are expected to produce 2.3 billion pounds of almonds this year – an increase of 1.3 percent from last year’s crop – despite concerns about freezing weather during the almond bloom. With more almonds come more co-products, meaning the almond industry is looking for possible ways to make the best use of everything grown in an orchard.

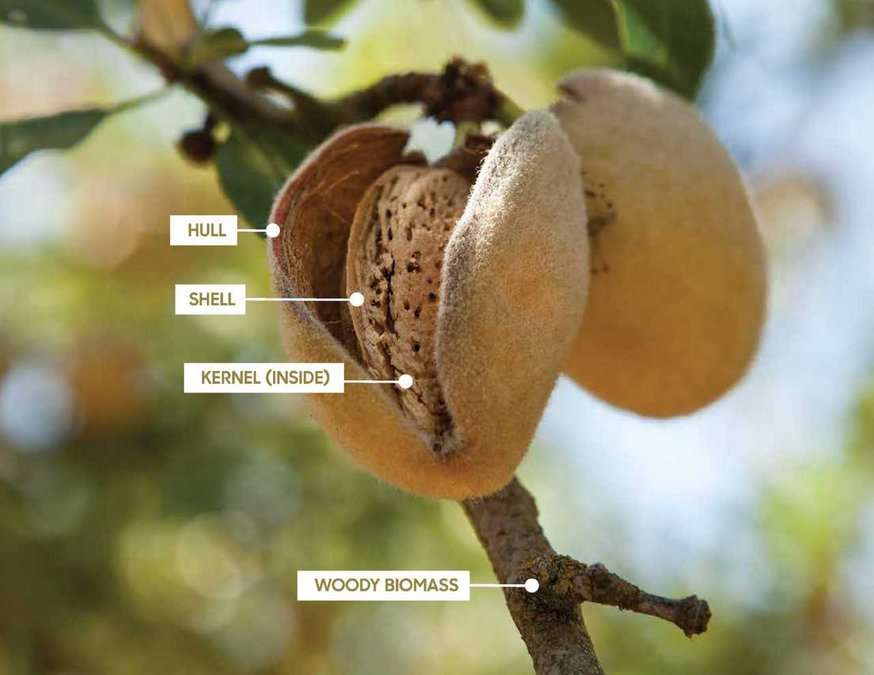

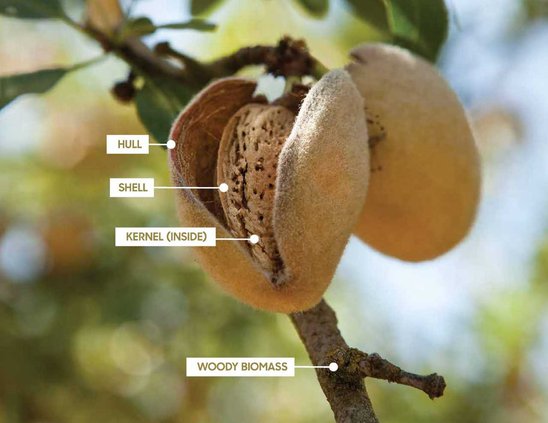

On every almond tree, there are four products: the kernel that we eat, and three other co-products. The tree itself and its woody biomass is one such co-product, which has a 25-year lifespan, the hard shell that protects the kernel is another and the soft, flexible hull found outside of the shell is the last.

For every pound of almonds produced in California, farmers are left with two pounds of hulls. Last year, almond farmers grew 2.1 billion pounds of kernels and another 4.3 billion pounds of hulls.

“It’s a lot of material,” Almond Board communications manager Danielle Veenstra said. “We’re able to use co-products in a variety of ways right now, but we see the world around us changing and we want to be prepared to have new uses for these things.”

The Almond Board has been funding almond co-product research since the 1970s, spurred by a desire to reduce the industry’s carbon footprint and better its production practices. It was then that the current uses we have for almond co-products were discovered, such as using hulls for dairy cattle rations and shells for livestock bedding. That was nearly fifty years ago, Veenstra said, and now research is accounting for the state’s declining dairy industry by finding different uses for retired trees, hulls and shells.

“We’re seeing all these shifts that are happening. The industry is growing, we have more co-products and the places we had traditionally sent them are changing as well,” Veenstra said. “That’s really led to where we are today as far as doubling down in this research area to find even better – and hopefully value-added – uses for these co-products.”

As the market value of hulls and shells shrinks along with the dairy industry, farmers have started looking for other uses – some of which may be in their own fields, research is beginning to show. While spent trees under are usually sent to “cogeneration” plants under current practice where they are used to create energy, research at University of California, Davis, is experimenting with whole-orchard recycling.

This practice sees trees at the end of their lifespan chipped up and spread out evenly on the orchard floor. It’s then tilled into the land and serves as nutrients for the soil where a new crop of almond trees will be planted. While it’s still a relatively new idea and there’s much research that has yet to be done on the topic, there are countless possibilities for benefits, Veenstra said.

“We need to make sure we observe the orchards for a while and make sure the practice isn’t spreading any diseases unintentionally, or that it’s not harming the future orchard in any way, but we also know that there’s a lot of potential for things like a greater water holding cap in the soil and improved soil health thanks to organic matter,” she said. “We’re looking at what the benefits are, but also how it affects the trees and the viability of a healthy orchard.”

Another co-product use that farmers may take advantage of one day is the use of orchard materials to fight pests, also known as biosolarization. This method takes the hulls, shells and woody biomass and puts it back into the orchard’s soil. The soil is then soaked with water and a tarp is placed over the area, creating an anaerobic environment that kills soil pests, like nematodes, which chew on almond trees’ roots.

Biosolarization is seen by researchers as an alternative to fumigating, Veenstra said.

“Pests can impact the orchard’s overall lifespan, and it’s important to us that growers set up their orchards for success,” she said. “This approach could be an alternative to traditional fumigation that happens in orchards and that’s really exciting.”

Growers and hullers looking for other ways to cash in on their spent hulls and shells will appreciate the research coming out of the USDA’s lab in Albany, where shells are being used to strengthen recycled plastic. To do this, shells are put through torrefaction, a thermal process which converts the shells into a powdery, coal-like material, which is then mixed with post-consumer recycled plastics to create a new, stronger plastic.

“We’ve used this to create flower pots that don’t melt or warp in the sun, or to create compostable dinnerware that doesn’t have problems with boiling points,” Veenstra said.

There is also interest surrounding sugar in almond’s hulls, she added, which is also being researched in Albany. The almond is more closely related to the peach, the plum and the nectarine than it is to the walnut or pistachio, meaning that the almond’s hull is the almond’s “fleshy” part and contains sugar.

Researchers have learned how to extract sugar from almond hulls and are now looking at using the product to create teas, hard ciders, beers and more. The almond hull sugar is even being used in preliminary studies on bees, where researchers are gauging the insects’ response to hull sugar as opposed to high fructose corn syrup – the supplemental food bees typically receive in the winter. Early reports say the bees prefer almond hull sugar, said Veenstra.

“We’re looking really widely at potential uses for these co-products so that we can come up with and determine if it’s good for the end user,” she said. “If we created a value scorecard on which methods are a value to the industry and to us, we would see which ones are going to net out best and pursue those ones.”

From 1977 to today, the Almond Board community has invested $1.6 million in 58 research projects to ensure that all almond co-products are put to beneficial use. This research will ensure that the farmers of today are prepared for tomorrow, Veenstra said.

“We want to find the best use for these co-products, take a zero-waste approach and make sure that everything we’re growing is being put to really good use,” she said. “And if they have added value, that’s an added bonus for us.”