The phone chimes and Turlock City Councilmember Rebecka Monez is on the line.

She doesn’t have time for hellos.

“My constituents are willing to talk, but you can’t use their real names,” insists Monez, an attorney who represents Turlock's heavily Hispanic District 2 and is squeezing in a call between court appearances. “They’re scared.”

During the 2024 presidential campaign, then-candidate Donald Trump promised to begin mass deportations of illegal immigrants on Day 1 of a second term. And when that second term began on Monday, President Trump signed a bevy of executive orders dealing with immigration. Ever since, Monez has been receiving calls from constituents who want to know what it all means.

“People shouldn’t have to live in fear,” she says.

Monez constituents’ Mateo and Lupe — not their real names — met with the Journal in the office of the local church in which they were married last summer. The marriage, however, is not recognized civilly. That’s because putting your name on official paperwork isn’t something you’re keen to do when one of you is an undocumented immigrant.

“I get very scared because he travels for his job,” says Lupe, 20, who has dark brown eyes and long black hair. “Recently, because of more sightings of immigration, we had to come up with quick signals so he can let me know that he might be in trouble.”

Lupe is a natural-born U.S. citizen, as are her mother and siblings; her father holds a Permanent Resident (Green) Card. She graduated from local schools and works in the food-service industry. But being a natural-born citizen doesn’t make her feel completely comfortable.

“Our lives are here, our families are here,” says Lupe. “All of our family has come to Turlock and said that this is where they want to stay. But nobody’s ever helped us really feel comfortable here.”

Mateo, 23, has a tousled mop of hair and a sleepy expression that belies a jovial personality and dry wit. Also a product of local schools, he works in sales and has been in the U.S. since he was a little boy, brought here by his single mother. He speaks English well, but with a slight accent.

“My mom had me when she was a teenager and she just wanted a better life for us,” says Mateo, who is one of about 12 million undocumented immigrants residing in the U.S., according to statistics provided by Modesto-based attorney Maegen Fulenchek, who handles immigration cases.

Typically, Fulenchek says, it takes five to six years for an immigration case to make its way through the courts.

“I think it’s reasonable for undocumented immigrants to have their antennae up right now,” says Fulenchek, who has been practicing law for nearly 10 years and was an immigration paralegal three years before that. “There’s no reason to panic, but there are certain things that everyone should know as far as dealing with law enforcement.”

Fulenchek encourages undocumented immigrants to be fully aware of their rights when dealing with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE): you do not have to answer questions; you may ask for an attorney; you do not have to show identification or answer the door unless a judicial warrant is presented; you may ask immigration officials to slide the warrant under the door to be inspected.

“I’m informing undocumented immigrants of their rights, and not how to beat a case,” says Fulenchek. “Ethically, I can’t advise anyone how to beat a criminal case, but I can advise anybody of their legal, constitutional rights.”

Stanislaus County District Attorney Jeff Laugero, Sheriff Jeff Dirkse, and Turlock Police Chief Jason Hedden all have pointed out recently that their agencies have no role in prosecuting federal immigration laws, or targeting undocumented immigrants.

“Our jurisdiction covers the prosecution of those that violate state and local laws,” Laugero said in an email. “Some offenders may be immigrants, but that is not a consideration when we file a case… We only look at what happened that led to their arrest, not who they are, not if they’re rich or poor, their race or any other consideration, including their immigration status.

“Furthermore, for those that are victims of crime, or witnesses to crime, we encourage them to report the crime to law enforcement regardless of their immigration status.”

Dirkse says that Senate Bill 54 limits local law enforcement agencies in their dealings with undocumented immigrants.

“Let’s say someone who’s an illegal immigrant is booked on a misdemeanor drunk driving charge,” says Dirkse. “Their fingerprints will be uploaded into the system. ICE is then notified, and ICE says that they want the guy. By law, I cannot turn him over to ICE for that low-level offense.”

If the accused were to have a history of serious felony convictions — murder, assault, rape, sex trafficking, drug dealing, burglary, etc. — then ICE would have a legitimate claim to that person.

The same holds true for Hedden and the Turlock Police Department.

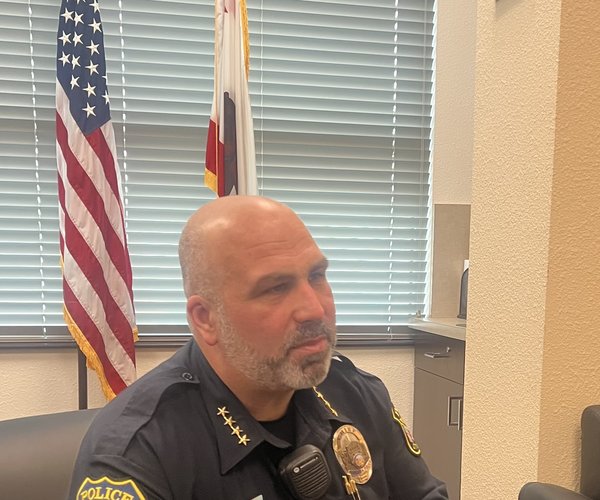

“We go after bad guys … those that are bringing in fentanyl, those that are doing human trafficking, those that are targeting and victimizing our community,” says Hedden. “Our primary mission is getting guns, drugs and bad people off the street. And that’s why we have the new street crimes unit in place. It’s a shift in resources that we’ve dedicated to protect our community. Immigration is not our role.”

In other words, bad guys, regardless of immigration status, are in the crosshairs of local law enforcement. Law-abiding citizens, regardless of immigration status, are not.

Dirkse says he’s tired of the issue being politicized and thinks the biggest mistake is not separating the issues of immigration and border security.

“When you leave your home, what do you do? You lock your house, you set the alarm. That’s border security,” says Dirkse. “Your house is just like our country. Keep the bad guys out. At the same time, you invite friends and family, and their friends and families, into your home. That’s immigration. Good people are welcome.”

Dirkse says that from 2021-2023, his office had more than 300 legitimate detainers placed by ICE for hard-core felons.

“You know how many they picked up?” asks Dirkse. “One. One out of about 310 or 320. So how about we start there?”

That’s a statistic that irritates Monez.

“My formal stance on immigration is like my stance on homelessness,” says Monez. “There are homeless people that choose lawlessness, and there are homeless people who have suffered an unfortunate circumstance, and have nowhere to go. Immigration is no different. There are hardcore criminals here illegally and we need to deport them. But there are undocumented immigrants here who have committed no crimes, are hard-working, are living peaceful lives, and they deserve a path to citizenship. And you can absolutely quote me on that because that’s real life.”

Mateo and Lupe, meanwhile, hope they can obtain for him the proper paperwork that will lead to citizenship. One option would be for Lupe, the U.S. citizen, to apply for a spousal visa, and then Mateo would have to travel back to his hometown to retrieve it. Trouble is, Mateo was born in Sinaloa, the nerve center of the Mexican drug cartel.

“We don’t want to put his name and birthplace on a legal document,” says Lupe. “We’re afraid that immigration might assume he’s a member of the cartel.”

Then there’s the problem of dealing with the cartel.

“Right now, there are gunmen at the borders of his hometown that don’t let people in,” says Lupe. “And if they found out he’s been living in the U.S., and wants to come back, they might hold him for ransom.”

Not the typical problems that most newlyweds face.

Until the young couple can sort out his immigration issues, they’ll continue living in the shadows, not sure what the next day holds.

“This is where we want to be,” says Mateo. “Everything is here.”