In the wake of record-breaking rain and snow this winter, experts have cautioned that despite the deluge, California remains in a drought.

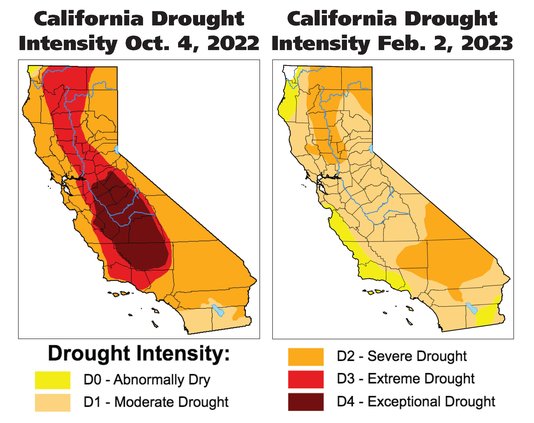

According to the United States Drought Monitor there are five categories of drought: abnormally dry (D0), moderate drought (D1), severe drought (D2), extreme drought (D3) and exceptional drought (D4). Most of California is now experiencing moderate conditions. And while some places remain in a severe drought, some are classified as being abnormally dry. All this is a big improvement from last month, when much of the state was in severe drought, and 7 percent of California was dealing with exceptional drought.

Currently, no region of the state is experiencing D3 or D4 conditions.

The past three years have been the driest stretch since records have been kept. Recovering from that would take two wet years — 2023, which is on its way to being a wet year, plus next year — in California and a decade or more of wet years for the Colorado River Basin, said Roger Bales, a professor of engineering at UC Merced who specializes in water and climate research. The Colorado River Basin supplies water to seven states, including California, and also provides water to Mexico.

But, of course, the recent storms have done plenty to help the situation, refilling reservoirs and recharging groundwater supplies.

Last month, Turlock Irrigation District said that it will be able to provide farmers their full allotment of 48" for irrigation, meaning that they have exited “operational” drought stage.

Several of the state's reservoirs are at or above historical averages for this time of year, according to the California Department of Water Resources.

As of Feb. 2, Don Pedro Reservoir contained more than 1.44 million acre feet of water, with a capacity just over 2 million acre feet. That’s higher than its historical average and, at about 75 percent of capacity and above its historical average.

But few reservoirs are close to capacity, and for those that are, the situation can quickly change, depending on how many more storms come through — and how hot it gets during the summer.

Reservoirs provide seasonal storage for water supply, in addition to storage to reduce downstream flooding, Bales said.

"In wetter years, such as water year 2017, they will store as much winter/spring runoff as they can for water supply, while still leaving some space for flood control in case of heavy rainfall," he said. "In drier years, they may not fill all of their water-supply storage capacity. Such was the case in water-year 2022 (Oct. 1, 2021 — Sept. 30, 2022), resulting in very reduced deliveries of irrigation and municipal water during the dry season."

In wetter years, there is some carry-over storage, meaning water is left over from one season into the next. But there isn't often very much of it.

"Think of it like a monthly checking account that has monthly income and expenses, where one may need to reduce spending in lean months to maintain a positive balance at the end of the month, but can spend more when income is higher, and maybe have a little carryover," Bales said.

To sufficiently fill the reservoirs, the state needs "two to three more big storms" before the end of March, Bales said.

More rainfall also will help replenish water under the surface of the earth in the soil and weathered bedrock.

"Water has drained out of the subsurface during dry years, and that is being naturally refilled as rain and snowmelt seeps into the ground," Bales said. "So, there is a little less runoff the year after a dry year than after a wet year, while the headwaters replenish this subsurface water that the forests depend on to survive dry seasons and dry years.”