BY JESSE VAD

San Joaquin Valley Water

Last month marked the 10-year anniversary of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, (SGMA) which aims to bring severely over pumped aquifers back into balance by 2040.

Even with more than $1 billion already spent, two groundwater subbasins on probation and enforcement actions being challenged in court, some state officials say the hard part is just beginning.

And the San Joaquin Valley is ground zero for what’s coming.

SGMA was passed in 2014 during a devastating drought that left thousands of domestic wells dry in the San Joaquin Valley. The law seeks to regulate groundwater pumping through local control. To that end, it mandated the creation of a new layer of government, groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) to create and impose plans for regulation.

“It was pretty anxious times,” said Paul Gosselin, deputy director of sustainable groundwater management at the state’s Department of Water Resources (DWR.) “The first 10 years, I think for both the department and local agencies, was trying to unravel a very complicated law.”

Years of progress

But everyone has come a long way over the past decade, he added. The state and local agencies have a wealth of data and tools to monitor and understand groundwater far better than was possible 10 years ago, said Gosselin.

Local agencies have also stepped up during drought, committed to fixing dry domestic wells and have met state deadlines for plans and projects, he said.

“The state provided upwards of half a billion dollars to local agencies, which has really increased groundwater recharge projects, land transition to recharge and some other land uses, as well as the start and development of some demand management (pumping reduction) programs in basins that really need that,” said Gosselin. “So, those are really some of the things that position us a lot better, one: for this changing climate. But two: to have the structure and foundation to achieve groundwater sustainability and have groundwater uses not be subjected to undesirable results.”

Undesirable results is SGMA lingo for things like plummeting water tables, wells going dry, water quality issues and subsidence, or land sinking as too much water is pulled out of the ground.

While the challenge was understanding the law in the early days, 10 years in, the new challenge is full implementation, said Gosselin. Trying to get projects started, securing funding, transitioning land out of agriculture and the impacts that could have on the industry, will be difficult, he added.

“It’s been the easy part, believe it or not,” said Gosselin. “It’s going to be increasingly challenging.”

Turlock area efforts

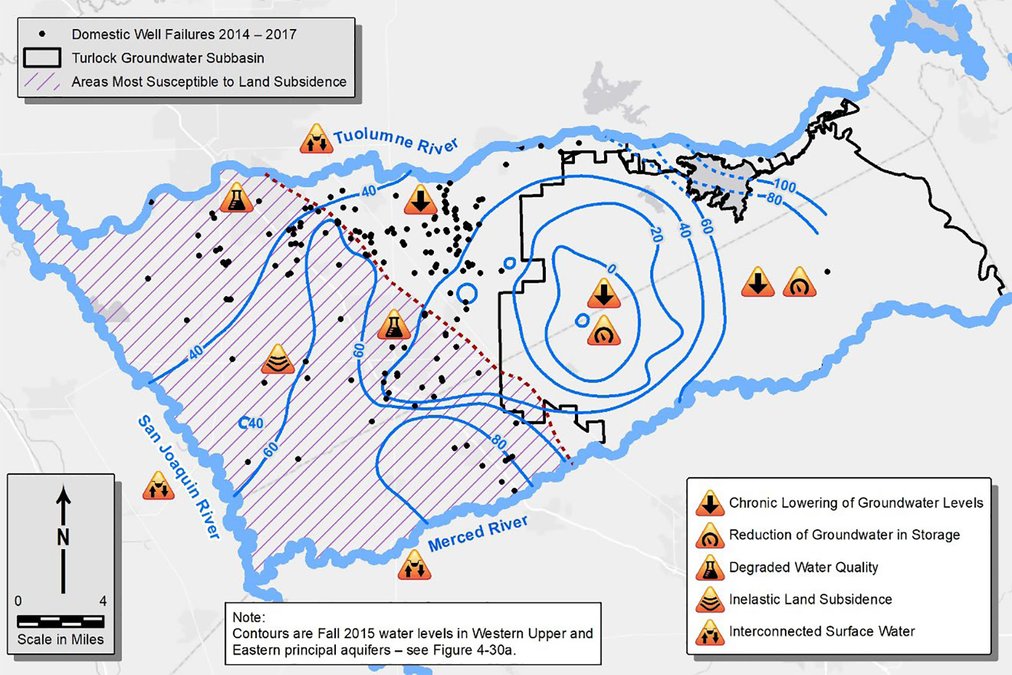

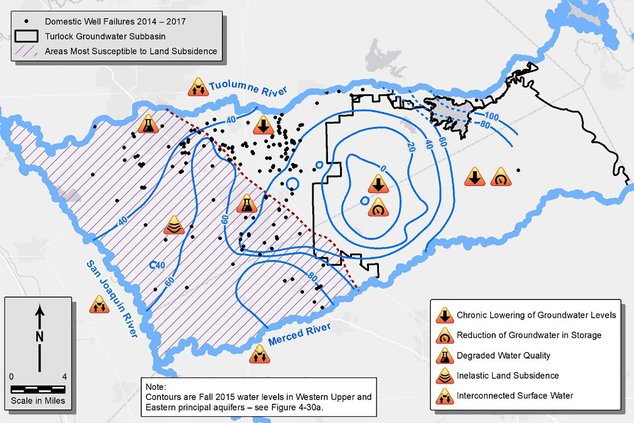

The Turlock Subbasin covers about 348,160 acres (about 544 square miles) in the northern portion of the San Joaquin Valley Groundwater Basin. Subbasin boundaries are defined by the Tuolumne River on the north, the Merced River on the south, and the San Joaquin River on the west. The eastern boundary approximates the contact between Subbasin sediments and the crystalline basement rocks of the Sierra Nevada foothills.

Water supply in the subbasin is provided by two primary sources: surface water from the Tuolumne and Merced rivers, and groundwater pumped from the subbasin. The Tuolumne River provides the largest supply of surface water. Turlock Irrigation District diverts water from the Tuolumne River at La Grange Dam and conveys it into the subbasin primarily for agricultural supply. The Merced River serves as an additional source for agriculture irrigation and is provided by Merced ID both to the Turlock Subbasin and the Merced Subbasin to the south. Most of the surface water supply is provided for agricultural beneficial uses in the West Turlock Subbasin. Agricultural beneficial uses in East Turlock Subbasin rely primarily on groundwater. Drinking water supply in the Subbasin – including municipal, urban communities, small water systems and domestic wells – is primarily provided by groundwater.

The West Turlock Subbasin Groundwater Sustainability Agency and the East Turlock Subbasin GSA submitted their Groundwater Sustainability Plan to California’s Department of Water Resources in January 2022.

On Jan.18 of this year, the California Department of Water Resources provided comments on the Turlock Subbasin’s Groundwater Sustainability Plan following a two-year review period. The Turlock Subbasin’s GSP was determined to be incomplete by DWR and was required to be revised. A revised plan was submitted in July.

Two deficiencies were identified by DWR. The first of these involves provision of sufficient information to support the selection of sustainable management criteria for chronic lowering of groundwater levels (particularly, analysis of potential impacts on wells). The second involves provision of sufficient details on the proposed projects and management actions to mitigate overdraft in the subbasin and provide a feasible path to achieve sustainability. The revised 2024 GSP aimed to correct these deficiencies by the implementation of a well mitigation program no later than Jan. 31, 2025, and the implementation starting in 2025 of a Groundwater Demand Reduction Plan that will arrest chronic groundwater level decline by 2027 and achieve sustainable management by 2042.

Challenges ahead

Another always present concern moving forward, is the unpredictability of climate.

“We have ongoing subsidence challenges that we need to address,” said Karla Nemeth, director of DWR. “If we have a big slug of very, very dry years without these storm events punctuating things, that sort of hastens the acuteness of the problem.”

While many water managers and officials agree that sustainability will be achieved by 2040, Nemeth admitted Mother Nature will have a hand in how on track management stays in the coming years.

Still, the difference between now and a decade ago is drastic, according to Nemeth.

“We know so much more about what’s happening below our feet,” said Nemeth.

Using technology such as airborne electromagnetic surveys to see the composition of the earth beneath the surface, for example, is one tool that has provided data that wasn’t available 10 years ago, said Nemeth.

Nemeth acknowledged SGMA has been difficult for many in agriculture.

“The goal isn’t pain for pain’s sake,” said Nemeth. “The goal is to have a resource that is in good shape and is reliable, because we are going to have deeper droughts and we are going to need to rely on groundwater.”

Too early to tell

For some of those outside of ag, it’s too early to tell whether sustainability is within reach in less than 20 years.

The culture of groundwater pumping is changing, said Nataly Escobedo Garcia, policy coordinator for nonprofit Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability. But more change is needed, she added.

The state’s probationary processes have already been held up in court, most recently in Kings County, which Escobedo Garcia described as “delay tactics.” It won’t be possible to avoid SGMA, she said. And if that means legislatively giving more teeth to the state to be able to enforce the law, then that’s what might have to happen, she added.

Regardless, the way groundwater was used for the past 20-30 years cannot continue into the figure, said Escobedo Garcia. “Otherwise, we’ll simply be in a race to the bottom.”

SJV Water is an independent, nonprofit news site dedicated to covering water in the San Joaquin Valley.

Turlock Journal Editor Kristina Hacker contributed to this article.